Editors’ note: today’s guest entry has been kindly developed by Dr. John Aubrey Douglass, Senior Research Fellow – Public Policy and Higher Education at the Center for Studies in Higher Education (CSHE) at the University of California – Berkeley, and currently visiting professor at the University of Campinas (Unicamp, Brazil). John Douglass is the co-editor of Globalization’s Muse: Universities and Higher Education Systems in a Changing World (Public Policy Press, 2009), and author of The Conditions for Admissions (Stanford Press 2007) and The California Idea and American Higher Education (Stanford University Press, 2000; published in Chinese in 2008).

Editors’ note: today’s guest entry has been kindly developed by Dr. John Aubrey Douglass, Senior Research Fellow – Public Policy and Higher Education at the Center for Studies in Higher Education (CSHE) at the University of California – Berkeley, and currently visiting professor at the University of Campinas (Unicamp, Brazil). John Douglass is the co-editor of Globalization’s Muse: Universities and Higher Education Systems in a Changing World (Public Policy Press, 2009), and author of The Conditions for Admissions (Stanford Press 2007) and The California Idea and American Higher Education (Stanford University Press, 2000; published in Chinese in 2008).

This contribution reflects the author’s recent analysis of the past and future of California’s higher education system: see ‘Re-Imagining California Higher Education‘ Center for Studies in Higher Education (CSHE), UC Berkeley, ROPS Oct 2010; ‘Chaos to Order and Back: the Cal Master Plan@50‘ CSHE ROPS May 2010. This piece should also be read in conjunction with James Vernon’s piece (‘The end of the public university in England‘) in GlobalHigherEd (a genuine ‘hit’ given the traffic it generated) as well as ‘Browne’s gamble: the future of universities‘ by Stefan Collini in the London Review of Books. Mark Blyth of the Watson Institute of International Studies (Brown University) has also helped shed light on the current round of austerity budgets sweeping the globe via this striking new video (aptly titled Austerity) which we posted today just below John Douglass’ entry.

Kris Olds & Susan Robertson

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

To a degree unmatched among developed economies, Britain’s new government has decided to embrace austerity in government spending. How is one to interpret the actions of the fresh, young Prime Minister David Cameron and Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne? For one, its seems like a legitimate, if perhaps an overreaching, reaction to government debt.

One sees a similar reaction among those nations hit hardest by the Great Recession, with governments with previously existing large deficits and economies built on the housing bubble and consumer debt, including the US, Ireland, and Portugal.

To varying degrees, these nations are now entering a profoundly anti-Keynesian moment, taking a bet that the private sector will quickly make up for public investment and services to help turn their economies around.

A second interpretation? The austerity drive and its severity in England is part of a larger political attack; an opportunity to severely reduce government services and costs not to be missed – a version of the “starve the beast” approach championed now for decades in the United States largely by Republicans.

With a public increasingly wary of the government’s ability to navigate the treacherous waters of the Great Recession, and a building campaign and sense that government debt is a bigger concern than, say, immediate job creation, conservatives on both sides of the Atlantic are attempting to seize an opportunity to cut government spending across the board.

And that is what you see in England. Across the board cuts of some 40 percent are, to say the least, draconian. There are only a few exceptions, including funding for the national health care system. But otherwise, there has been no effort, it seems, to pick and choose winners based on, to imagine another path, long-term effect economic development or educational attainment rates.

Under Gordon Brown’s labour government, higher education suffered relatively minor cuts to research, but always under the specter that more significant cuts were on their way.

Time will tell if Conservative policymaking, with seeming consent of the Liberal Democrats will be a grand economic success. England has a large debt problem, no doubt; but one already sees some signs of economic growth in England’s economy – arguably the partial result of stimulus funding under Brown. Why not a more measured program of cuts over time, marginal increases in revenues, with priority funding where you get long-term economic and social benefits?

But never mind that discussion; what will be the consequences for British higher education?

Like other government services, the university sector is to experience a 40 percent cut in funding from the national government, to be accomplished over a four-year period. Lord Browne’s new report on the future of England’s higher education system, a commission report launched before the recent Conservative victory, has accepted the Cameron government’s austerity demands, and the backroom desire of the Russell Group, that a partial answer is to generously lift the cap on university tuition fees.

The Browne report recommended, and the Tories have formally accepted in their recent budget announcement, the notion of a new cap: a £6,000 per year “threshold,” up from £3,250, to a maximum of £9,000 in “exceptional circumstances” – read, the Russell Group with a collection of some 20 self-appointed elite universities, including Oxbridge.

From a foreign, US perspective, the added edict of the Tories to shift what HEFCE university funding remains to science and engineering fields, and reducing funding to the humanities and social sciences is to seriously meddle with what should normally be internal funding decisions of institutions. Universities now must dig into their fee income if they want to keep these programs in place, placing pressure on their vibrancy, and in some cases existence.

And what is the response of other members of England’s higher education community? It’s a diffuse lot, but Universities UK President Steve Smith, seems to think it is all a done deal, and that the new fee cap “allows universities to replace a large part of the lost state funding for teaching,” by way of post-graduate contributions.

“We believe,” explains Smith, “that this package of proposals represents the best available funding system for universities, given the £2.9bn cuts to the higher education budget announced in the Spending Review.”

Of course, you get the typical response of students and the growing ranks of dissatisfied university faculty. The University and College Union and the National Union of Students just held a decent sized protest rally in London, with estimates of the number of participants varying from 25,000 to over 50,000. A good amount of the anger is pointed to the Liberal Democrats, who pledged to oppose any increase in university fees.

In my view, the magnitude of the cuts and proposed increases in fees is extremely problematic– a “leap before you look” approach to policymaking that is fairly common in England. Most studies show that you can move to a moderate to high fee, and high bursary/financial aid system with possibly positive influence on socio-economic access. But it also must be a process done slowly, not on the fly, and certainly not in the time frame demanded by Prime Minister Cameron and his party.

How can such dramatic and rapid cuts be absorbed without negatively influencing educational attainment rates, and the vitality and moral of most of England’s higher education institutions? It seems that the “exceptional” fee model may very well benefit the elite institutions, but what is the effect in the larger system, and the not so elite?

Of course, I don’t fully know the answer; nor, might I say, does anyone else. As a matter of reference, however, I can say with a small drip of sarcasm, welcome to the club. Most states in the US have been going through a similar financial restructuring characterized by sizable reduction in government support. California in particular has suffered the wrath of steep, sudden, and unanticipated declines in revenue.

Here is a short story focused on the experience in California.

The Case of California

The dire situation for US higher education is most acute in the state of California, presenting an exaggerated yet common narrative. With some 35 million people, California is the largest state (nearly twice the size of New York in population) and has an economy that ranks among the top ten in the world if it were a country.

The state also has the largest concentration of high technology companies in the American union. Unlike England, California is projected to experience large-scale population growth, with an estimated population of 60 million by 2050.

At the same time, California’s famous public higher education system is undergoing a possibly significant redefinition, driven solely by severe budget cuts and without a long-term strategic plan.

In terms of access and graduation rates, the grand success of California’s pioneering public higher education system, and its Master Plan, is in many ways a thing of the past. Where California was always among the top states in high school graduation rates, in access to higher education, and in degree completion rates, the state now ranks among the bottom ten in most categories.

In short, it is modestly good in access, and an extremely low performer in degree production.

The causes are many, including declining investment in education generally, low high school graduation rates, and high attrition rates among students in higher education – a pattern that correlates with a high number of part-time students in California and an inadequate financial aid model at the national and state level, affecting California’s ranking in a number of funding and performance indicators (see accompanying box).

Note California’s general low ranking in the US; then note that the US has been declining relative to economic competitors among the 32 mostly developed member nations of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Economic Development (OECD).

Note California’s general low ranking in the US; then note that the US has been declining relative to economic competitors among the 32 mostly developed member nations of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Economic Development (OECD).

The Great Recession has accelerated California’s decline and may have a significant impact on educational attainment levels in the state – probably a real decline in the short-term.

Declining state revenues has brought a near collapse in the coherence of California’s higher education system. Public funding per student has plummeted and, for the first time, students normally eligible for the University of California and California State University systems have been denied admissions.

Over the past decade, both UC and CSU have been taking on more and more students that are, in the parlance of university administrators, “unfunded.” The University of California has some 15,000 undergraduates receive no corresponding funding from the state; at a campus like Berkeley, some 18 percent of undergraduate are “unfunded” by the state.

California’s Community Colleges could not absorb students who were refused admission to UC and CSU. A budget cut of $825 million for these colleges has led to wholesale cutting of courses and shrinking enrollment capacity, translating into some 200,000 or more prospective Community College students being denied access.

What have been the on the ground, in the trenches effects of the age of austerity?

The Case of the University of California

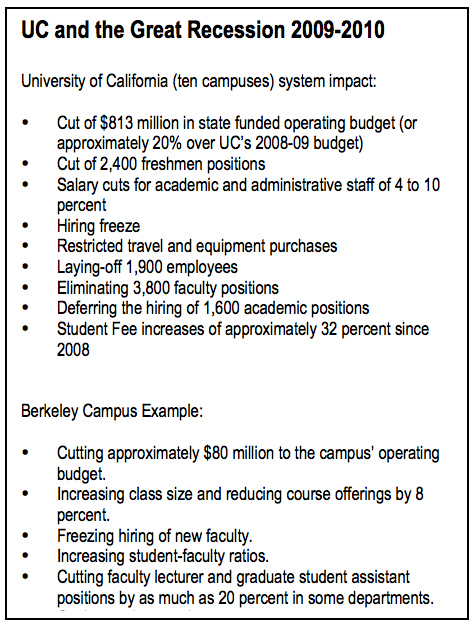

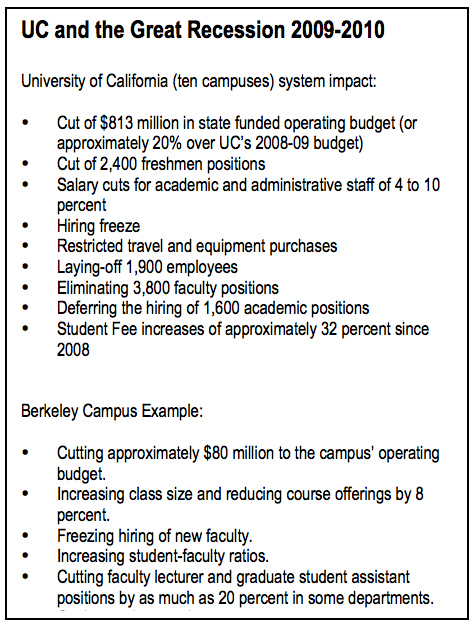

At the University of California, which includes ten campuses and has the reputation of being one of the most productive and high quality university systems in the world (some six campuses are members of the prestigious Association of American Universities), budget cuts have resulted in large fee increases – not unlike what England will soon experience.

The UC Board of Regents increased fees by 15 percent in Spring 2010, and then did it again in for Fall 2010 – an increase of over 32 percent over less than a two-year period. UC undergraduates now pay about $11,000 a year in fees and campus-based costs; room and board can add $16,000. Graduate and professional students pay more.

Despite a slight increase in funding for UC proposed in the state budget for this year – a glimmer of hope of a marginal resurrection of public funding – UC President Mark Yudof just proposed another 8 percent increase in UC student fees, “to help maintain the university’s excellence.” The increase would take effect in fall 2011.

Like the emerging bursary scheme in England, a third of all fees is returned to lower income students in the form of financial aid. The plan is to expand the so-called “Blue and Gold Opportunity Plan,” a financial aid promise that UC students from families earning below $80,000 annually can attend tuition-free – up from the $70,000 threshold used last year for financial aid.

Like the emerging bursary scheme in England, a third of all fees is returned to lower income students in the form of financial aid. The plan is to expand the so-called “Blue and Gold Opportunity Plan,” a financial aid promise that UC students from families earning below $80,000 annually can attend tuition-free – up from the $70,000 threshold used last year for financial aid.

But these large increases in tuition and fees have not been enough to cover the huge loss of public funding for UC – again, a story that most British higher education institutions (HEIs) will likely experience. State support per student at UC has declined by roughly half in the past two decades.

The other ways to cut? Besides cutting enrollment, the most common path to fiscal austerity is to cut faculty and administrative support staff positions. This drives up student to faculty ratios. At UC, class sizes are up by about 25 percent.

The university has and is eliminating programs, reducing library hours, cutting extracurricular activities, cutting support services, and hiring not only fewer teaching faculty, but also student assistants and part-time student employees. See the accompanying box for a list of impacts for the UC system as a whole, and then at the Berkeley campus where I am.

Take these examples, and magnify them several times and you get a sense of what is happening at the California State University (CSU) which enrolls twice as many students as UC, and is a teaching focused university, and the primary source of teachers and engineers in California.

Large-scale cuts in staffing have resulted in large-scale cuts in courses offered. Reduced course sections will extend graduation time for many students. “Currently, 48% first-time freshmen graduate within six years, which may decrease when students are unable to get into courses needed to graduate,” noted a recent report by the California Postsecondary Education Commission.

The “Brazilian Effect”

Looking beyond UC and CSU, another macro effect is what I call the “Brazilian Effect”: when public higher education can not keep pace with growing public demand for access and programs, For-Profits rush to fill that gap, and become a much larger provider. This is the pattern in many developing economies – Brazil where more than 50 percent of student enrollment is in For-Profit institutions; Korea, and Poland also reflect this model.

To be fair, Brazil has recently made significant strides to regulate its non-public providers through a new accreditation process, and has pushed the development of three-year colleges oriented toward vocational degree programs.

California is on the opposite side of that curve. There is currently a steep rise in enrollment in For-Profits in California precisely because of cuts in enrollment at UC, CSU, and the Community Colleges.

In essence, California is increasingly having the characteristics of both a developed and an under-developed economy, i.e. a society with high rates of near poverty level incomes, low high school graduation rates, limited access to public higher education, and low production of tertiary degrees.

As my Berkeley colleague James Vernon recently wrote in GlobalHigherEd, one may see a similar phenomenon in England as a nascent British “For-Profit sector awaits in the wings hungry to buy up or ‘rescue’ the publics that will surely fail in the years ahead.”

Some growth in the For-Profit sectors in California is inevitable and good. A diversified market of higher education providers is an essential component to expanding access and graduation rates. But there is evidence that much of that sector is of low quality and productivity and very expensive for the student and the federal and state governments which provide grants and loans to students.

Some 80 percent or more of For-Profit operating expenses come from taxpayer funded student grants and loans. Particularly at the traditional college cohort of 18 to 24 year-olds, very high attrition is common among these institutions and, in turn, low degree production rates – even lower than comparable public institutions. In 2008-09, students at for-profits accounted for nearly 10 percent of all higher education students, but received 23 percent of all federal student aid, roughly $23.9 billion, according to a recent Congressional report.

The Obama administration has proposed new and fairly minimal rules regarding the eligibility of For-Profits for federal student aid that have extremely high attrition rates and extremely low job placement histories. The industry, with most companies traded in the stock market, is vehemently opposed and, in the midst of Congressional hearings on the bill, has launched a massive and deceptive add campaign to defeat the bill. In this case, it is about money, and specifically the prospect of declining profits and declining stock prices; it is also about the possibility of further federal restrictions of the flow of tax dollars to these private institutions. [According to The Economist (9 Sept 2010), “Shares in Apollo Group, which owns the University of Phoenix, are worth half what they were at the start of 2009. The Washington Post Company has lost nearly one-third of its value since April. Shares in Corinthian Colleges have fallen 70% in the same spell.”]

Nevertheless, even with new regulatory controls on the worst of the For-Profits, many of which are predatory, recruiting students who cannot afford large loan debts and with low job probabilities, the market will remain robust for this growing sector of California’s higher education system. There is a role for For-Profits, but it is a matter of balance.

The current surge in enrollment is largely the unintended consequence of an inability to properly structure and grow public higher education; yet, at the same time, these private enterprises operate largely on taxpayers funding. My primary concern is that this is a default position that funnels growing higher education demand to For-Profits.

California needs a more strategic approach.

Trying to Think Big

It’s a bit of a leap, but I offer in a recent research paper, ‘Re-Imagining California Higher Education,’ a reflection on the macro-problems and pathway for California to once again place its higher education system at the vanguard of being both a high access and high quality network of universities and colleges. Here is a short synopsis.

Most critics and observers of California’s system remain focused on incremental and largely marginal improvements, transfixed by the state’s persistent financial problems and inability to engage in long-range planning for a population that is projected to grow from approximately 37 million to some 60 million by 2050.

Most critics and observers of California’s system remain focused on incremental and largely marginal improvements, transfixed by the state’s persistent financial problems and inability to engage in long-range planning for a population that is projected to grow from approximately 37 million to some 60 million by 2050.

At the same time, President Obama has set a national goal for the US to once again have among the highest educational attainment rates in the world. This would require the nation to produce over 8 million additional degrees; California’s “fair share” would be approximately 1 million additional degrees. A number of studies indicate that California’s higher education system will not keep pace with labor needs in the state, let alone affording opportunities for socioeconomic mobility that once characterized California.

California needs to re-imagine its once vibrant higher education system. I offer a vision of a more mature system of higher education that could emerge over the next twenty years; in essence, a logical next stage in a system that has hardly changed in the last five decades.

Informed by the history of the tripartite system, its strengths and weaknesses over time, and the reform efforts of economic competitors throughout the world who are making significant investments in their own tertiary institutions, I offer a “re-imagined” network of colleges and universities and a plan for “Smart Growth.” I paint a picture that builds on California’s existing institutions, predicated on a more diverse array of institutional types, and rooted in the historical idea of mission differentiation.

This includes setting educational attainment goals for the state; shifting more students to 4-year institutions including UC and CSU; reorganizing the California Community Colleges to include a set of 4-year institutions, another set of “Transfer Focused” campuses, and having these colleges develop a “gap” year program for students out of high school to better prepare for higher education.

It also encompasses the idea of creating a new Polytechnic University sector, a new California Open University that is primarily focused on adult learners; and developing a new funding model that recognizes the critical role of tuition, and the market for international students that can generate income for higher education and attract top talent to California.

There is also a need to recognize that for the US to increase degree attainment rates, the federal government will need to become a more engaged partner with the states. For the near and possibly long-term, most state governments are in a fiscally weakened position that makes any large-scale investment in expanding access improbable. Because of the size of its population alone, California is the canary in the coalmine. If the US is to make major strides toward President Obama’s goal, it cannot do it without California.

Ask Mr. Cameron

In conclusion, it will be interesting to ask a few questions to our government leaders in California, in Washington, and in Whitehall. In the midst of the global recession, how have national governments viewed the role of higher education in their evolving strategies for economic recovery?

Demand for higher education generally goes up during economic downturns. Which nations will proactively protect funding for their universities and colleges to help maintain access, to help retrain workers, and to mitigate unemployment rates? And which nations have simply made large funding cuts for higher education in light of the severe downturn in tax revenues?

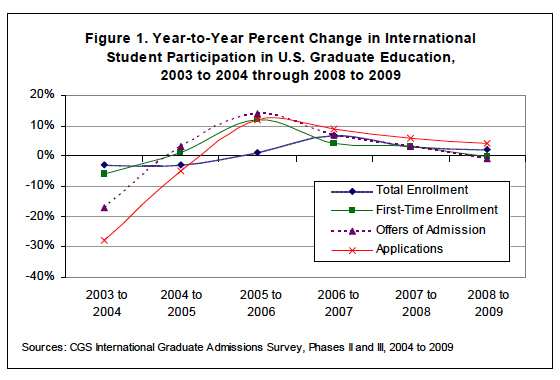

One might postulate that the decisions made today and in reaction to the “Great Recession” by nations in this difficult economic era will likely accelerate global shifts in the race to develop human capital.

Let’s see how England and the US fare.

John Aubrey Douglass

What struck me? Well, the Olympic opening ceremony flagged the music, the landscapes (urban and rural), the family dynamics, the cultural politics, and the institutions (including the National Health Service, NHS) I encountered on a regular basis as a foreign student. Britain is relatively small so students can travel around easily and experience diverse geographies including the bustling global city of London (via a cheap shoppers’ express bus), deindustrialized parts of the Midland’s Black Country, and subtly different ‘rural idylls’ via train, car and foot. I lived in Bristol with my wife Janice, also a Canadian, and we have abundant memories of experiences in these diverse geographies, as well as with fellow students, advisors (in my case the superb duo of Nigel Thrift & Keith Bassett), quirky staff, and an astonishing range of Bristolians in the city. These positive experiences were all jolted back to life via segments of the opening ceremony last night.

What struck me? Well, the Olympic opening ceremony flagged the music, the landscapes (urban and rural), the family dynamics, the cultural politics, and the institutions (including the National Health Service, NHS) I encountered on a regular basis as a foreign student. Britain is relatively small so students can travel around easily and experience diverse geographies including the bustling global city of London (via a cheap shoppers’ express bus), deindustrialized parts of the Midland’s Black Country, and subtly different ‘rural idylls’ via train, car and foot. I lived in Bristol with my wife Janice, also a Canadian, and we have abundant memories of experiences in these diverse geographies, as well as with fellow students, advisors (in my case the superb duo of Nigel Thrift & Keith Bassett), quirky staff, and an astonishing range of Bristolians in the city. These positive experiences were all jolted back to life via segments of the opening ceremony last night. British cities were also served by real bookstores (thank you, Blackwell’s Bookshop) during our stay and it was in these that we sourced our newborn son’s first picture books on top of all sorts of other books. The respect for literature, and the imagination, was also evident in the opening ceremony.

British cities were also served by real bookstores (thank you, Blackwell’s Bookshop) during our stay and it was in these that we sourced our newborn son’s first picture books on top of all sorts of other books. The respect for literature, and the imagination, was also evident in the opening ceremony.