Source: UNCTAD (2005) World Investment Report 2005: Transnational Corporations and the Internationalization of R&D, Geneva: UNCTAD.

Month: October 2007

Mexican university now turns to the US for higher education students

Much of the mapping and analysis of transnational student mobility in higher education tends to focus on ‘south’ to the ‘north’ movements. However, recently GlobalHigherEd has been profiling some very interesting south-south movements, for instance with a highly entrepreneurial Malaysian university now establishing itself in Botswana.Today the Chronicle of Higher Education reported on another interesting reversal – this time with a large Mexican university now seeking students in the US and Canada:

Spotting a ripe market and a growing Hispanic population, the National Autonomous University of Mexico is steadily strengthening its foothold in the United States and Canada-one of the first inroads northward by a Latin American university.

While the National Autonomous University of Mexico (National Autonomous University of Mexico) has always had some presence in the US however this has tended to be directed to cultural activities.

Now, however UNAM sees that the Hispanic population in the USA might benefit those Mexicans and Latinas who have left their home countries and want to continue studying or complete a degree – in the USA or in Canada.

The Chronicle reports that the biggest campus is in San Antonio – in a two story building donated by the Texas city government. In exchange, UNAM professors teach the municipal employees Spanish and help with translation services. Other programs are run in Chicago and Quebec.

These developments suggest the benefits might work in several directions; for students of Hispanic decent, for local governments, and also for those wanting to learn Spanish. They also bring to light a range of new players into the field of transnational education, though the motivations of the students and the outcomes of various initiatives may well be quite divergent.

However they also highlight the fact that a comparative advantage in transnational higher education may not always be English, or cost of living, or indeed student fees (as we have previously reported), but the possibilities of exploiting ethnic agglomeration in a transnational knowledge space.

Susan Robertson

Graphic feed: China rises to #1 position (total number of university graduates/yr)

Note: WEI = World Education Indicators (WEI) Programme, a UNESCO initiative that analyses the progress made by 19 middle-income and developing countries.

Source: UNESCO (2007) ‘Highlights from the UIS report: Education Counts Benchmarking Progress in 19 WEI Countries’, September.

OECD’s science, technology and industry scoreboard 2007

Every two years the OECD publishes a Science, Technology and Industry Scoreboard. Yesterday it released its 2007 assessment of trends of the macroeconomic elements intended to stimulate innovation: knowledge, globalization, and their impacts on economic performance.

Every two years the OECD publishes a Science, Technology and Industry Scoreboard. Yesterday it released its 2007 assessment of trends of the macroeconomic elements intended to stimulate innovation: knowledge, globalization, and their impacts on economic performance.

GlobalHigherEd has taken a look at the major findings of the report and highlights them below. These indicators of ‘innovation’ presumed to lead to ‘economic growth’ reveal a particular set of assumptions at work . For instance:

- Investment in ‘knowledge’ (by which the OECD means software and education) has increased in most OECD countries.

- Expenditure on R&D (as a % of GDP) in Japan (3.3%) and the EU (1.7%) picked up in 2005 following a drop in 2004. However, in the US expenditure in R&D declined slightly (to 2.6% in 2005 from 2.7% in 2001). China is the big feature story here, with spending on R&D growing even faster than its economy – by 18% per year over the period 2000-2005.

- Countries like Switzerland, Belgium and English speaking countries (US, UK etc) have a large number of foreign doctoral students…with the US having the largest number. About 10,000 foreign citizens obtained a doctorate in S&E in the US in 2004/5 and represented 38% of S&E doctorates awarded.

- Governments in OECD countries are putting into place policy levers to promote R&D – such as directing government funds to R&D through tax relief.

- Universities are being encouraged to patent their innovations, and while the overall share of patents filed by universities has been relatively stable, this is increasing in selected OECD countries – France, Germany and Japan.

- European companies (EU27) finance 6.4% of R&D performed by public institutions and universities compared to 2.7% in the US and 2% in Japan.

- China now ranks 6th worldwide in their share of scientific publications and has raised its share of triadic patents from close to 0% in 1995 to 0.8% in 2005, though the US, Europe and Japan remain at the forefront. However, the US and the emerging economies (India, China, Israel, Singapore) focus upon high tech industries (computers, pharmaceuticals), whilst continental Europe focuses on medium technologies (automobiles, chemicals).

- In all OECD countries inventive activities are more geographically concentrated – in an innovation cluster – as in Silicon Valley and Tokyo.

- There has been a steady diffusion of ICT across all OECD countries – though take up if broadband in households varies, with Italy and Ireland showing only 10-15% penetration.

- Across all OECD countries, use of the internet has become standard in businesses with over 10 employees.

These highlights from the Scoreboard reflects a number of things. First, it is a particular (and very narrow) way of looking at the basis for developing knowledge societies. Knowledge, as we can see above, is reduced to software and education to develop human capital.

Second, there is a particular way of framing science and technology and its relationship to development – as in larger levels of expenditure on R&D, rates of scientific publications, use of ICTs.

Third, it is assumed that the combination of inventions, patents and innovations will be the necessary boost to economic growth. However, this approach privileges intellectual property rights over and above other forms of invention and innovation which might contribute to the intellectual commons, as in open source software.

Finally, we should reflect on the purpose the Scoreboard. Not only is a country’s ‘progress’ (or ‘lack of’) then used by politicians and policymakers to argue for boosting investment and performance in particular areas of science and technology, as in recruiting more foreign students into graduate programs, or the development of incentives such as the promise of an EU Blue Card to ensure the brainpower stays in the country, but the Scorecard is a pedagogical tool. That is, a country ‘learns’ about itself in relation to other players in the global economy and is given a clear message about the overall direction it should head in if it wants to be a globally competitive knowledge-based economy.

Susan Robertson

Constructing knowledge/spaces in the Middle East: KAUST and beyond

Further to our recent entries on Qatar Education City, NYU Abu Dhabi, and ‘Liberal education venturing abroad: American universities in the Middle East‘, Wednesday’s Financial Times and today’s New York Times both have informative pieces about Saudi Arabia’s attempt to rapidly construct a new “MIT” in the desert. The Institute of the Future’s informative blog, which we happily just discovered, also has an illuminating profile of this development. And also see Beerkens’ Blog for another illuminating analysis.

The King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), a US$12.5 billion university, is being built from scratch, with a formal groundbreaking ceremony on 21 October 2007. The development of new universities, and foreign campuses or programs in Saudia Arabia, is clearly an indicator of a desire for significant economic and cultural shifts amongst select elites. This said the development process is an incredibly complicated one, and riddled with a series of tensions, mutually supporting objectives, and some challenging contradictions. It is also a very geographic one, with supporters of such developments seeking to create new and qualitatively different spaces of knowledge consumption, production and circulation. The Financial Times had this to say:

Kaust plans to bring western standards of education to a Saudi institution amid an environment of academic freedom. The university, loosely based on Aramco’s gated community where the kingdom’s social mores are watered down, is set to push the boundaries of gender segregation in an education system where men and women very rarely meet.

The university plans to guarantee academic freedom, bypassing any religious pressure from conservative elements, by forming a board of trustees that will use recently approved bylaws to protect the independence of the university.

“It’s a given that academic freedom will be protected,” says Nadhmi al-Nasr, an Aramco executive who is Kaust’s interim president.

His assertion has yet to be tested but the mix of academic freedom and social liberalism could spark criticism despite the king’s patronage.

Dar al-Hikma, a private women’s college in Jeddah, has faced trouble from those who reject social liberalism. “Many have opposed us but this is different – the king is behind Kaust,” says the Dr Suhair al-Qurashi, the college’s dean.

At a broader scale KAUST is also being designed to generate an interdependent relationship with King Abdullah Economic City, a US$27 billion mixed use development project that is situated near the university. And at an even broader scale KAUST is designed to help transform the structure of the Saudi economy. Nadhmi A. Al-Nasr (KAUST’s interim president) put it this way:

“It is the vision of King Abdullah to have this university as a turning point in higher education,” he said. “Hopefully, it will act as a catalyst in transforming Saudi Arabia into a knowledge economy, by directly integrating research produced at the university into our economy.”

As is the case with other new universities being developed in the 1990s and 2000s (e.g., Singapore Management University‘s development was strongly shaped by Wharton faculty, especially Janice R. Bellace), the Saudis are acquiring intellectual guidance and advice from a variety of non-local academics and administrators, including a veritable Who’s Who of senior university officials from around the world. Link here for further media and blog coverage of KAUST.

The myriad of changes in the Middle Eastern higher ed landscape are ideal research topics, and they are more than deserving of attention given their scale, and potential for impact, success and/or failure. But who is conducting such research? We might be wrong but not a lot of substantial analysis seems to have been written up and published to date. If you are reading this and you are doing such work let us know – we’d be happy to profile your writings here in GlobalHigherEd, and/or engage in some international comparative dialogue.

Kris Olds

Malaysian university campuses in London and Botswana (and Mel G. too)

The vast majority of foreign campuses tend to be created by Western (primarily US, UK, & Australian) universities in countries like Malaysia (e.g., University of Nottingham), the United Arab Emirates (e.g., NYU Aub Dhabi), China (e.g., University of Nottingham, again), South Africa, and so on. As Line Verbik of the OBHE notes in an informative 2006 report titled The International Branch Campus – Models and Trends:

The majority of branch campus provision is from North to South or in other words, from developed to developing countries, a trend, which is also found in other types of transnational provision. US institutions clearly dominate, accounting for more than 50% of branch campuses abroad, followed by Australia (accounting for approximately 12% of developments), and the UK and Ireland (5% each). A range of other countries, including Canada, the Netherlands, Pakistan and India, have one or two institutions operating campuses abroad. South to South activity is rare, some few examples being the Indian and Pakistani institutions operating in Dubai’s Knowledge Village.

Post-colonial relations are often an underlying factor for they facilitate linkages between former colonial powers and their colonial subjects. This is not surprising in some ways, though the relationship between former colonial powers and colonial subjects is a complicated one. Singapore, for example, has been shifting its geographic imagination away from the UK and towards the USA for the last decade, driven as it is by a perception that the US has better quality universities, and also the growing number of now well-placed politicians and government officials who have US vs. UK degrees.

Post-colonial dynamics aside, ideological and regulatory shifts also enable foreign universities to open up campuses in territories previously closed off to “commercial presence” (using GATS parlance). While there are huge variations in the nature of how ideological and regulatory transformations unfold (peruse UNCTAD’s annual World Investment Report to acquire a sense of variation by country, and the general liberalization shift), it is clear that the majority of countries are now more open to the presence of foreign universities within their borders. This said the mode of entry that they choose to use, or are forced to use (via regulations), is also very diverse.

In tracking the phenomena foreign/branch/overseas campuses, it is always valuable (in an analytical sense) to hear of unexpected developments that cause one to pause. One such unexpected outcome is the March 2007 opening of a Malaysian university campus in London, one of the world’s most expensive cities. Yesterday’s Guardian has an interesting profile of the key architect (Dr. Lim Kok Wing) of this university (Limkokwing University of Creative Technology (LUCT). LUCT is a private for profit university with a flair for out of the norm (for universities) PR: witness the excitement spurred on by the presence of Mel Gibson, for example, when he was brought to the Malaysian campus of LUCT.

The Guardian profile does a good job of explaining some of the rationale for the campuses, but also some of Lim’s personal style which is an intangible but important part of the development process, and seems to be even reflective in the titles of the degrees LUCT offers.

Coverage of Lim Kok Wing’ s overseas venture in Botswana (which opened up in March 2007 too) is also worth following for it sheds light on how higher education entrepreneurs are exploiting a country’s brand name (Malaysia in this case), as well as the relatively difficult higher education context many African countries are experiencing. It is also in line the Malaysian government’s strategy – of expanding its share of the global higher education market (see our earlier report).

The Botswana campus took Lim only five months to establish, and over a thousand students “swarmed” its campus during opening day. We’ve heard that there are just over a 1,000 students, with some 5,500 students being planned for in 2008 at the Botswana campus. Entrepreneurs like Lim are effectively mining fractured seams in the global higher education landscape, for they operate at a level than enables the to identify openings for the creation of institutions (and student tuition income stream). Lim puts it this way:

“However, as a developing country, Malaysia is better able to understand the needs of other developing nations. It is therefore in a better position to deliver British education to the developing world.”

So a Malaysian university, providing a Malaysian education in London, and a British education in Botswana (to students from over 100 countries)…the global higher ed landscape is indeed changing…

Kris Olds & Susan Robertson

Graphic feed: Private expenditure (%) on tertiary education in 41 key countries (2004)

Source: UNESCO (2007) ‘What do societies invest in education? Public versus private spending‘, Factsheet No. 04, October. [in support of the Global Education Digest 2007]

EU Blue Cards: not a blank cheque for migrant labour – says Barroso

The global competition for skilled labor looks like getting a new dimension – the EU is planning to issue “blue cards” to allow highly skilled non-Europeans to work in the EU. On Tuesday 23 October José Manuel Barroso, President of the European Commission, announced plans to harmonize admission procedures for highly qualified workers. As President Barroso put it:

The global competition for skilled labor looks like getting a new dimension – the EU is planning to issue “blue cards” to allow highly skilled non-Europeans to work in the EU. On Tuesday 23 October José Manuel Barroso, President of the European Commission, announced plans to harmonize admission procedures for highly qualified workers. As President Barroso put it:

With the EU Blue Card we send a clear signal: Highly skilled people from all over the world are welcome in the European Union. Let me be clear: I am not announcing today that we are opening the doors to 20 million high-skilled workers! The Blue Card is not a “blank cheque”. It is not a right to admission, but a demand-driven approach and a common European procedure.

The Blue Card will also mean increased mobility for high-skilled immigrants and their families inside the EU.

Member States will have broad flexibility to determine their labour market needs and decide on the number of high-skilled workers they would like to welcome.

With regard to developing countries we are very much aware of the need to avoid negative “brain drain” effects. Therefore, the proposal promotes ethical recruitment standards to limit – if not ban – active recruitment by Member States in developing countries in some sensitive sectors. It also contains measures to facilitate so-called “circular migration”. Europe stands ready to cooperate with developing countries in this area.

Further details are also available in this press release, with media and blog coverage available via these pre-programmed Google searches. As noted the proposed scheme would have a common single application procedure across the 27 Member States and a common set of rights for non-EU nationals including the right to stay for two years and move within the EU to another Member State for an extension of one more year.

The urgency of the introduction of the blue card is framed in terms of competition with the US/Canada/Australia – the US alone attracts more than half of all skilled labor while only 5 per cent currently comes to the EU. This explanation needs to be seen in relation to two issues which the GlobalHigherEd blog has been following: the competition to attract and retain researchers and the current overproduction of Maths, Science and Technology graduates. Can the attractiveness of the EU as a whole compete with the pull of R&D/Industrial capacity in the US and the logic of English as the global language? Related to this obviously is the recent enlargement to 27 Member States where there are ongoing issues around the mobility of labor within the EU? We will continue to look beneath the claims of policy initiatives to see the underlying contradictions in approaches. The ongoing question of the construction of a common European labor market and boosting the attractiveness of EU higher ed institutions may be at least as important here as the supposed skilled labor shortages.

Futurology demographics seem to be at the heart of the explanation of the need to intensify the recruitment of non-EU labour – according to the Commission the EU will have a shortage of 20 million workers in the next 20 years, with one third of the EU population over the age of 65. Interestingly though, there is no specification of the kinds of skill shortages that far down the line – the current concern is that the EU currently receives 85 % of global unskilled labour.

Barroso and the Commission continue to try to handle the contradictions of EU brain attractiveness strategies by the preferred model of:

- fixed term contracts;

- limitations on recruitment from developing countries in sensitive sectors; and,

- the potentially highly tendentious notion of ‘circular migration’.

High skilled labour is effectively on a perpetual carousel of entry to and exit from the labour market with equal rights while in the EU which get lost at the point of departure from the EU zone only to reappear on re-entry, perhaps?

According to Reuters the successful applicants for a blue card would only need to be paid twice the minimum wage in the employing Member State – and this requirement would be lifted if the applicant were to be a graduate from an EU higher education institution. Two things are of interest here then – the blue card could be a way to retain anyone with a higher education qualification and there are implications for the continuing downward pressure on wage rates for the university educated. It will be interesting to see how this one plays out in relation to the attractiveness of EU universities if a blue card is the implied pay-off for successful graduation.

Peter D. Jones

Apollo Group and the Carlyle Group form $1 billion joint venture to make investments in the international education services sector

GlobalHigherEd was established on 1 September 2007. Since then we have been profiling (often through the “graphic feed” mechanism) some of the broader structural forces, trends and outcomes that are emerging in the context of the globalization of higher education services.

These transformations are also evident in the form of news releases. On Monday 22 October these news releases (link to Apollo and Carlyle) were circulated at a global scale, extracts of which are pasted in below. This development highlights the nature of unmet demand for higher education services in select regions and countries, as well as the role of the private sector in providing (or planning to provide) higher education services when state capacity to provide said services is limited, by accident or design. See these links for further media and blog coverage regarding this significant development. Carlyle is the (in)famous private equity firm associated with numerous Washington DC political power-brokers. See Tegenlicht’s 48 minute long Dutch/English video The Iron Triangle – The Carlyle Group Exposed (2004), though also be sure to examine this February 2007 BusinessWeek analysis of how the Carlyle Group is now seeking to diversify its activities (and in the process become less of a political flashpoint).

Apollo, a listed firm (see its share history above), operates the US’ largest university – private for-profit University of Phoenix, with approx. 250,000 students. This news release comes one week after the Financial Times noted that US-based Bridgepoint Education is planning to enter the UK’s higher education scene, spurred on by the “level playing field” dynamic generated by top-up fees in the UK, and the relatively large proportion of foreign students who continue to be drawn to the UK (see this link for an interview with Bridgepoint’s CEO, and the OECD’s Education at a Glance 2007 for data on foreign student mobility patterns).

The press release about the formation of “Apollo Global” states:

Apollo Group and the Carlyle Group Form $1 Billion Joint Venture to Make Investments in the International Education Services Sector

PHOENIX & WASHINGTON–(BUSINESS WIRE)–Oct. 22, 2007–Apollo Group, Inc. (Nasdaq:APOL) (“Apollo Group” or the “Company”), and private equity firm The Carlyle Group (“Carlyle”), today announced that they have formed a $1 billion joint venture, Apollo Global, Inc. (“Apollo Global”). Apollo Global intends to make a range of investments in the international education services sector. Apollo Global will target investments and partnerships primarily in countries outside the U.S. with attractive demographic and economic growth characteristics. Apollo Group has committed up to $801 million and will own 80.1% of the joint venture. Carlyle has committed up to $199 million and will own 19.9% of Apollo Global. Investments and funding will be subject to approval by the respective investment committees of both Apollo Group and Carlyle. Apollo Global will be a consolidated subsidiary of Apollo Group and Greg Cappelli, Apollo Group’s Executive Vice President and Director will be Chairman of the subsidiary.

Commenting on the new venture, Greg Cappelli said, “We are very excited about this new joint venture and our partner, The Carlyle Group. Our core competencies in the education space, combined with Carlyle’s industry relationships and strategic assets across the global education sector, will allow us to successfully capitalize on the tremendous global opportunity that exists in the marketplace.”

Brian Mueller added, “We will continue to invest capital in our high return core domestic business, and through Apollo Global, we will also explore strategic and value creating global acquisition opportunities. Importantly, we reiterate that any investment must meet our disciplined investment criteria as we remain committed to creating long-term value for our shareholders.”

Brooke B. Coburn, Managing Director and Co-head of Carlyle Venture Partners III, L.P., said, “Global demand for higher education is strong. Apollo Group’s operational expertise coupled with Carlyle’s global network make this a powerful partnership.”

About Apollo Group, Inc.

Apollo Group, Inc. has been an education provider for more than 30 years, operating the University of Phoenix, the Institute for Professional Development, the College for Financial Planning, Western International University and Insight Schools. The Company offers innovative and distinctive educational programs and services at high school, college and graduate levels at 259 locations in 40 states and the District of Columbia; Puerto Rico; Alberta and British Columbia, Canada; Mexico and the Netherlands, as well as online, throughout the world.

About The Carlyle Group

The Carlyle Group is a global private equity firm with $75.6 billion under management committed to 55 funds. Carlyle invests in buyouts, venture & growth capital, real estate and leveraged finance in Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, North America and South America focusing on aerospace & defense, automotive & transportation, consumer & retail, energy & power, financial services, healthcare, industrial, infrastructure, technology & business services and telecommunications & media. Since 1987, the firm has invested $32.3 billion of equity in 686 transactions for a total purchase price of $157.7 billion. The Carlyle Group employs more than 900 people in 21 countries. In the aggregate, Carlyle portfolio companies have more than $87 billion in revenue and employ more than 286,000 people around the world. http://www.carlyle.com.

Also see 23 September Inside Higher Ed and Chronicle of Higher Education stories on this development.

Kris Olds

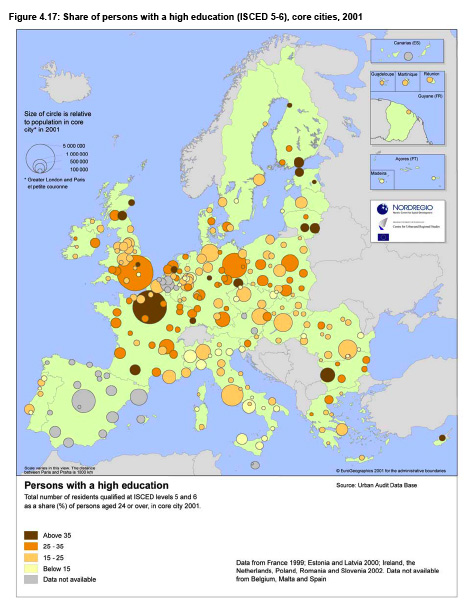

Graphic feed: Knowledge “nodes” = European city-regions?

Note: ISCED = International Standard Classification of Education

Source: European Union (2007) State of European Cities Report: Adding Value to the European Urban Audit, Brussels: European Union.

Globalizing universities: profiles and strategies (with a Duke example)

Over the course of the next year we will be developing some profiles of select institutions that are playing a key role in globalizing higher education systems via their transnational governance functions and objectives (e.g., the OECD), or via their actions (e.g., individual universities). Our entry about NYU two days ago is part of this focus, as is the 9 October Global Public University forum that we helped to organize. We will also be asking a range of institutions, including universities and consortia, to develop some self-profiles so as to let them speak in their own voices versus us speaking on their behalf. We will ensure that their representations are as analytical as possible, and that there is some diversity in that nature of the types of institutions that will be profiled. Switzerland’s Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) is currently developing the first self-profile that we will post. Those of you interested in this theme should also keep track of the Chronicle of Higher Education‘s US-focused Global Campus initiative, as well as select Institute of International Education (IIE) publications.

The issue of how universities globalize is a key one to take account of when examining the construction of global knowledge/spaces. To be sure there are broader structural forces that are at work, forces including economic restructuring, ideological change that is leading to regulatory reform, social transformations, and technological change. But the actions of individual universities, firms, and organizations, mediated by the state, collectively helps to constitute these broader structural forces. And each of these individual actors, guided by people and personalities, has a distinctive take on the globalization process. As we noted, NYU is now fully pursuing the Network model with its new campus in Abu Dhabi. Duke University is another institution with a variety of globalizing activities underway. The President of Duke University (Richard H. Brodhead) gave an illuminating speech (to Duke faculty) about this topic yesterday, and it is worth reading.

Duke is one of the universities that, through its actions (e.g., a joint Duke-National University of Singapore Graduate Medical School; see their new building to the left), is reaching out across global space, and concurrently enabling Singapore to pursue its emerging ‘global schoolhouse’ development framework. One element of the speech is particularly worth highlighting: how a university moves from an assortment of intra-university unit-led global initiatives, to ensuring that these actions help to achieve collective university wide goals, while at the same time the university better (and more efficiently) supports the myriad of activities that are taking place within said units, while ensuring that a globally recognized identity is constructed. Duke is, of course, a global anomaly; a very well-resourced private (non-profit) institution. And the context for the origin of the speech is unclear. However, there are still insights to be acquired by assessing how and why a globally active university like Duke does what it does. We’ll close off with a relatively lengthy quote here from Duke’s President:

Deluged by my examples, you might by now be saying: It’s amazing, I grant you! So isn’t Duke already international enough? I would reply as follows. I take delight in the vision and activity Duke has displayed to date. I also recognize our obligation not just to keep adding to our list of programs, but to work with what we have to give it depth and substance. (In American universities, the list of showy memoranda of understanding with international partners is far longer than the list of substantive relationships that have followed.) I also recognize that Duke’s international development entails tradeoffs with other, equally legitimate university goals, choices that need to be clearly envisioned and intelligently made. But I also believe there is important further work to do to take us to the next level of development as a global university.

One step is very obvious. I would never advocate central control and direction of Duke’s international efforts: the interest, commitment and inventiveness of actual individuals is the absolute precondition for these programs’ success. But we do need more centralized information about our ventures. We have programs exploring possible partnerships in countries (even in cities) where Duke already has an institutional presence that our new Duke ambassadors often know nothing about. Before we go forward, it would help to be able to know what’s already going on.

Second, as our international activities become more numerous and complex, we need to build the infrastructure to support them. Every Duke presence around the globe brings us new contacts, new visibility, new educational opportunity—but also new challenges of financial management, legal arrangement, and liability. It is inefficient at best, and dangerous at worst, for us to expect all our separate units to be able to manage these difficulties on their own. Going forward, they will require a higher level of institutional attention and a stronger system of institutional support.

There are other infrastructural issues as well. The way our local budgets are set up does not make it easy for different schools and departments to team up to envision new international ventures. I also wonder whether our faculty appointments system is structured to greatest advantage for an increasingly globalized intellectual world. At a dinner hosted by the provost this summer, the deans fell into speculation on the idea of an “international professor”—a person who would spend significant time here with the understanding that they would regularly spend time elsewhere, building bridges with a Duke connection. Let me not fail to mention that to continue to attract top student talent, Duke must increase international student financial aid.

Third, and this is my main point, we need our international efforts to be more concerted and strategic. Most of our projects to date have arisen through entrepreneurial activity by separate units. This is the key source of institutional creativity, and it will remain so. But the time comes to ask if these often-vibrant parts could not add up to a more coherent whole, a concerted activity that would advance this whole institution’s mission, with benefits for each part. More than institutional efficiency is at stake. This is a question of how we render the distinctive service this university could provide and how we make Duke known around the world.

Kris Olds

Is the EU on target to meet the Lisbon objectives in education and training?

The European Commission (EC) has just released its annual 2007 Report Progress Towards the Lisbon Objectives in Education and Training: Indicators and Benchmarks. This 195 page document highlights the key messages about the main policy areas for the EC – from the rather controversial inclusion of schools (because of issues of subsidiarity) to what has become more standard fare for the EC – the vocational education and higher education sectors.

As we explain below, while the Report gives the thumbs up to the numbers of Maths, Science and Technology (MST) graduates, it gives the thumbs down to the quality of higher education. We, however, think that the benchmarks are far too simplistic and the conclusions drawn not sufficiently rigorous to support good policymaking. Let us explain.

The Report is the fourth in a series of annual assessments examining performance and progress toward the Education and Training 2010 Work Programme. These reports work as a disciplinary tool for Member States as well as contributing to making the EU more globally competitive.

To those of you unfamiliar with EC ‘speak’ – the EC’s Work Programme centers around the realization of 16 core indicators (agreed in May 2007 at the European Council and listed in the table below) and benchmarks (5) (also listed below) which emerged from the relaunch of the Lisbon Agenda in 2005.

Chapter 7 of this Report concentrates on progress toward modernizing higher education in Europe, though curiously enough there is no mention of the Bologna Process – the radical reorganization of the degree structure for European universities which has the US and Australia on the back-foot. Instead, three key areas are identified:

- mathematics, science and technology graduates (MST)

- mobility in higher education

- quality of higher education institutions

With regard to MST, the EU is well on course to surpass the benchmark of an increase in the number of tertiary graduates in MST. However, the report notes that demographic trends (decreasing cohort size) will slow down growth in the long term.

While laudable, GlobalHigherEd notes that it is not so much the number of graduates that are produced which is the problem. Rather, there are not enough attractive opportunities for researchers in Europe so that a significant percentage move to the US (14% of US graduates come from Europe). The long term attractiveness of Europe (see our recent entry) in terms of R&D is, therefore, still a major challenge.

With regard to mobility (see our earlier overview report), the EU has had an increase in the percentage of students with foreign citizenship. In 2004, every EU country, with the exception of Denmark, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary and Slovakia, recorded an increase in the % of students enrolled with foreign citizenship. Austria, Belgium, Germany, France, Cyprus and the UK have the highest proportions with foreign student populations of more than 10%.

Over the period 2000 to 2005 the number of students going to Europe from China increased by 500% (from 20,000 in 2000 to 107,000 in 2005; see our more detailed report on this), while numbers from India increased by 400%. While there is little doubt that the USA’s homeland security policy was a major factor, students also view the lower fees and moderate living costs in countries like France and Germany as particularly attractive. In the main:

- the countries of origin of non-European students studying in the EU largely come from former colonies of the European member states

- mobility is within the EU rather than from beyond the EU, with the exception of the UK. The UK is also a stand-out case because of the small number of its citizens who study in other EU countries.

Finally, concerning the quality of higher education, the Bologna Reforms are nowhere to be seen. Instead the EC report uses the Shanghai Jiao Tong Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWI) and the World Universities Ranking (WUR) by the Times Higher Education Supplement to discuss the issue of quality. The Shanghai Jiao Tong uses Nobel Awards, and citations indexes (e.g. SCI; SSCI) – however, not only is a Nobel Award a limited (some say false) proxy for quality, but the citation indexes systematically discriminate in favor of US based institutions and journals. Only scientific output is included in each of these rankings; excluded are other kinds of outputs from universities which might have an impact, such as patents, or policy advice.

While each ranking system is intended to be a measure of quality – it is difficult to know what we might learn when one (Times Higher) will rank an institution (for example, the London School of Economics) in 11th position while the other (Shanghai) ranks the same institution in 200th position. Such vast differences could only be confusing for potential students if they were using them to make their choices about a high quality institution. However, perhaps this is not the main purpose, and that it serves a more important one – of ratcheting up both competition and discipline through comparison.

League tables are now also being developed in more nuanced ways. In 2007 the Shanghai ranking introduced one by ‘broad subject field’ (see below). What is particularly interesting here is that the EU-27 does relatively well in Engineering/Technology and Computer Sciences (ENG), Clinical Medicine and Pharmacy (MED) and Natural Sciences and Mathematics (SCI) in relation to the USA, compared with the Social Sciences (where the USA outflanks it by a considerable degree). Are Social Sciences in Europe this poor in terms of quality, and hence in serious trouble? GlobalHigherEd suggests that these differences are likely a reflection of the more internationalized/Anglocized publishing practices of the science, technology and medical fields, in comparison to the social sciences, who are committed in many cases to publishing in national languages.

The somewhat dubious nature of these rankings as indicators of quality does not stop the EC using them to show that of the top 100 universities, 54 are located in the USA and only 29 in Europe. And again, the overall project of the EC is to set the agenda at the European scale for Member States by putting into place at the European level a set of instruments–including the recently launched European Research Council–intended to help retain MST graduates as well as recruit the brightest talent from around the globe (particularly China and India) and keep them in Europe.

However, the MST capacity of the EU outruns its industry’s ability to absorb and retain the graduates. It is clear the markets for students and brains are developing in different ways in different countries but with clear ‘types’ of markets and consumers emerging. The question is: what would an EU ranking system achieve as a technology of competitive market making?

Susan Robertson and Peter Jones