Numbers, partnerships, linkages, and collaboration: some key terms that seem to be bubbling up all over the place right now.

Numbers, partnerships, linkages, and collaboration: some key terms that seem to be bubbling up all over the place right now.

On the numbers front, the ever active Cliff Adelman released, via the Institute for Higher Education Policy (IHEP), a new report titled The Spaces Between Numbers: Getting International Data on Higher Education Straight (November 2009). As the IHEP press release notes:

The research report, The Spaces Between Numbers: Getting International Data on Higher Education Straight, reveals that U.S. graduation rates remain comparable to those of other developed countries despite news stories about our nation losing its global competitiveness because of slipping college graduation rates. The only major difference—the data most commonly highlighted, but rarely understood—is the categorization of graduation rate data. The United States measures its attainment rates by “institution” while other developed nations measure their graduation rates by “system.”

The main target audience of this new report seems to be the OECD, though we (as users) of international higher ed data can all benefit from a good dig through the report. Adelman’s core objective is facilitating the creation of a new generation of indicators, indicators that are a lot more meaningful and policy-relevant than those that currently exist.

Second, Universities UK (UUK) released a data-laden report titled The impact of universities on the UK economy. As the press release notes:

Universities in the UK now generate £59 billion for the UK economy putting the higher education sector ahead of the agricultural, advertising, pharmaceutical and postal industries, according to new figures published today.

This is the key finding of Universities UK’s latest UK-wide study of the impact of the higher education sector on the UK economy. The report – produced for Universities UK by the University of Strathclyde – updates earlier studies published in 1997, 2002 and 2006 and confirms the growing economic importance of the sector.

The study found that, in 2007/08:

- The higher education sector spent some £19.5 billion on goods and services produced in the UK.

- Through both direct and secondary or multiplier effects this generated over £59 billion of output and over 668,500 full time equivalent jobs throughout the economy. The equivalent figure four years ago was nearly £45 billion (25% increase).

- The total revenue earned by universities amounted to £23.4 billion (compared with £16.87 billion in 2003/04).

- Gross export earnings for the higher education sector were estimated to be over £5.3 billion.

- The personal off-campus expenditure of international students and visitors amounted to £2.3 billion.

Professor Steve Smith, President of Universities UK, said: “These figures show that the higher education sector is one of the UK’s most valuable industries. Our universities are unquestionably an outstanding success story for the economy.

See pp 16-17 regarding a brief discussion of the impact of international student flows into the UK system.

These two reports are interesting examples of contributions to the debate about the meaning and significance of higher education vis a vis relative growth and decline at a global scale, and the value of a key (ostensibly under-recognized) sector of the national (in this case UK) economy.

And third, numbers, viewed from the perspectives of pattern and trend identification, were amply evident in a new Thomson Reuters’ report (CHINA: Research and Collaboration in the New Geography of Science) co-authored by the data base crunchers from Evidence Ltd., a Leeds-based firm and recent Thomson Reuters acquisition. One valuable aspect of this report is that it unpacks the broad trends, and flags key disciplinary and institutional geographies to China’s new geography of science. As someone who worked at the National University of Singapore (NUS) for four years, I can understand why NUS is now China’s No.1 institutional collaborator (see p. 9), though the why issues are not discussed in this type of broad mapping cum PR report for Evidence & Thomson Reuters.

Shifting tack, two new releases about international double and joint degrees — one (The Graduate International Collaborations Project: A North American Perspective on Joint and Dual Degree Programs) by the North American Council of Graduate Schools (CGS), and one (Joint and Double Degree Programs: An Emerging Model for Transatlantic Exchange) by the International Institute for Education (IIE) and the Freie Universität Berlin — remind us of the emerging desire to craft more focused, intense and ‘deep’ relations between universities versus the current approach which amounts to the promiscuous acquisition of hundreds if not thousands of memoranda of understanding (MoUs).

The IIE/Freie Universität Berlin book (link here for the table of contents) addresses various aspects of this development process:

The IIE/Freie Universität Berlin book (link here for the table of contents) addresses various aspects of this development process:

The book seeks to provide practical recommendations on key challenges, such as communications, sustainability, curriculum design, and student recruitment. Articles are divided into six thematic sections that assess the development of collaborative degree programs from beginning to end. While the first two sections focus on the theories underpinning transatlantic degree programs and how to secure institutional support and buy-in, the third and fourth sections present perspectives on the beginning stages of a joint or double degree program and the issue of program sustainability. The last two sections focus on profiles of specific transatlantic degree programs and lessons learned from joint and double degree programs in the European context.

It is clear that international joint and double degrees are becoming a genuine phenomenon; so much so that key institutions including the IIE, the CGS, and the EU are all paying close attention to the degrees’ uses, abuses, and efficacy. Thus we should view this new book as an attempt to both promote, but in a manner that examines the many forces that shape the collaborative process across space and between institutions. International partnerships are not simple to create, yet they are being demanded by more and more stakeholders. Why? Dissatisfaction that the rhetoric of ‘internationalization’ does not match up to the reality, and there is a ‘deliverables’ problem.

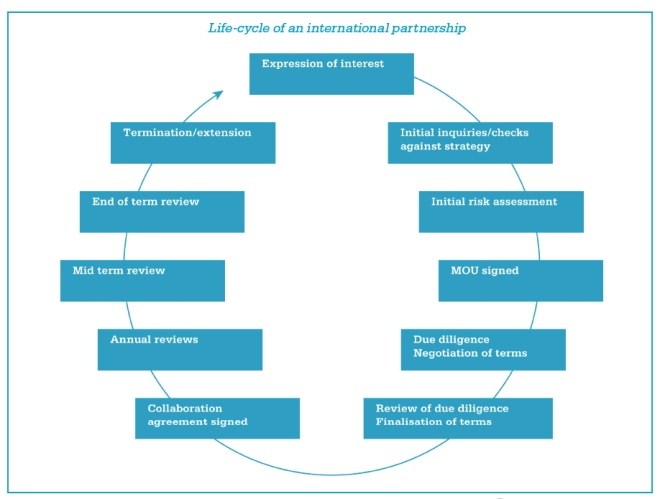

Indeed, we hosted some senior Chinese university officials here in Madison several months ago and they used the term “ghost MoUs”, reflecting their dissatisfaction with filling filing cabinet after filing cabinet with signed MoUs that lead to absolutely nothing. In contrast, engagement via joint and double degrees, for example, or other forms of partnership (e.g., see International partnerships: a legal guide for universities), cannot help but deepen the level of connection between institutions of higher education on a number of levels. It is easy to ignore a MoU, but not so easy to ignore a bilateral scheme with clearly defined deliverables, a timetable for assessment, and a budget.

The value of tangible forms of international collaboration was certainly on view when I visited Brandeis University earlier this week. Brandeis’ partnership with Al-Quds University (in Jerusalem) links “an Arab institution in Jerusalem and a Jewish-sponsored institution in the United States in an exchange designed to foster cultural understanding and provide educational opportunities for students, faculty and staff.” Projects undertaken via the partnership have included administrative exchanges, academic exchanges, teaching and learning projects, and partnership documentation (an important but often forgotten about activity). The level of commitment to the partnership at Brandeis was genuinely impressive.

The value of tangible forms of international collaboration was certainly on view when I visited Brandeis University earlier this week. Brandeis’ partnership with Al-Quds University (in Jerusalem) links “an Arab institution in Jerusalem and a Jewish-sponsored institution in the United States in an exchange designed to foster cultural understanding and provide educational opportunities for students, faculty and staff.” Projects undertaken via the partnership have included administrative exchanges, academic exchanges, teaching and learning projects, and partnership documentation (an important but often forgotten about activity). The level of commitment to the partnership at Brandeis was genuinely impressive.

In the end, as debates about numbers, rankings, partnerships, MoUs — internationalization more generally — show us, it is only when we start grinding through the details and ‘working at the coal face’ (like Brandeis and Al-Quds seem to be doing), though in a strategic way, can we really shift from rhetoric to reality.

Kris Olds